California State Fossil

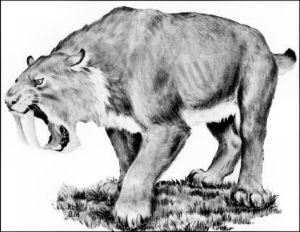

| Saber-toothed cat |

Smilodon californicus |

Adopted:September 25, 1973 |

Fossils are defined as "the remains" of life that existed and have been preserved by a natural process. The most likely "remains" to survive are hard parts such as shells, bones, and teeth.

In efforts to introduce natural historical contexts to a set of official state symbols including birds and flowers, citizens and/or citizen groups began teaming with legislators to include a general group of fossils, sometimes officially designated stones or dinosaurs.

This activity began in the sixties but picked up momentum in the eighties until, today, 80% of our 50 states have officially designated a state fossil symbol or emblem.

The designation of the saber-toothed cat (Smilodon californicus) as the official state fossil of California was preceded by a bill introduced in the 1972 General Assembly by Assemblyman W.Craig Biddle.

|

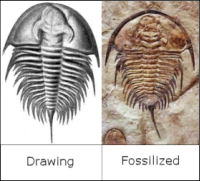

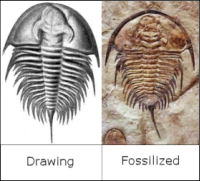

| Proposed California State Fossil: Trilobite |

On March 7, 1972 Assembly Bill No. 698 (AB 698) was read for the first time. It proposed that the trilobite, Fremontia fremonti, be adopted as the official state fossil of the State of California.

Trilobites are now-extinct marine organisms that existed during the Cambrian, Paleozoic, and Permian periods (between 544 and 248 million years ago).

Fremontia fremonti was named after early California explorer and U.S. Senator General John C. Fremont.

Biddle said that almost 2,000 museum curators, fossil collectors, and rockhounds endorsed Fremontia fremonti as the state fossil. The idea also had the backing of State Division of Mines and Geology and the University of California at Riverside.

In spite of the pressure of all of these endorsements, AB 698 never made it out of the Government Organization Committee to the Assembly floor for a vote.

Adoption of the California State Fossil

The next year, at the request of the Southern California Paleontological Society, another fossil bill was introduced in the Assembly.

|

Remains of Smilodon californicus

Credit: |

The measure, Assembly Bill No. 940 (AB 940), was introduced by Assemblyman Alan Sieroty. It did not support adoption of a trilobite as the state fossil, but proposed that the saber-toothed cat (Smilodon californicus) should be named to this honorary position.

Not as old as the trilobite introduced in 1972, the saber-toothed cat is said to have wandered the hills and valleys of California a mere 10,000 to 11,000 years ago. Very common in California, fossil bones of Smilodon californicus were discovered in 1881 in the Rancho La Brea tar pits, now in the heart of Los Angeles.

Since 1881, fossil bones of Smilodon californicus have been found in abundance preserved in the tar pits. In fact, the most famous and most concentrated deposit of Smilodon and other mammal remains is at the La Brea tar pits.

Assemblyman Sieroty noted that the saber-toothed cat was very common in California in its day and that this species was even named for the state. He pointed out that the most famous and most concentrated deposit of Smilodon and other mammal remains is at the La Brea tar pits and that many fine fossils have been taken from taken from the pits.

But Sieroty went a little too far for some when he referred to the saber-toothed cat as "a strong and majestic animal--symbolic of the grandeur of our state."

Napa County Rockhounds, Inc., who supported adoption of the trilobite as official fossil, jumped on Sieroty's claim, circulating excerpts from "The Fossils Book," by Carroll Fenton. The Fossils Book described an animal that was something less than majestic.

The book claimed the saber-toothed cat had "a clumsy build...probably ate carrion when he could find it and often devoured animals trapped in the sticky tar. In doing so, he himself might have become mired, but the Smilodon brain was too dull to weigh the chance of future disaster."

Napa County Rockhounds added that California, by adopting the trilobite, would distinguish itself with the oldest state fossil in the nation. By comparison, the Smilodon had not appeared until the day before yesterday.

Before the bill could be bogged down in the Assembly's Government Organization Committee, Sieroty brought Dr. Giles Mead, director of the L.A. Counting Natural History Museum and Dr. Dan Savage, a UC Berkeley professor of paleontology to testify on behalf of the cat. Their expert testimony seemed to impress and members of the committee voted 8-0 in favor of passage of the bill.

The Assembly followed suit and, on June 21, 1973, voted 72-0 without debate, to adopt Smilodon as the official state fossil of California.

The Assembly followed suit and, on June 21, 1973, voted 72-0 without debate, to adopt Smilodon as the official state fossil of California.

The Senate Government Organization Committee recommended passage of the bill unanimously (8-0) and on September 27, the bill passed the full Senate, 27-1. The one no vote was provided by now Senator W. Craig Biddle who, the year before, fought for adoption of the trilobite as the official state fossil in the California Assembly.

On September 25, 1973, Governor Ronald Reagan signed Assembly Bill No. 940 into law, designating the saber-toothed cat (Smilodon californicus) the official state fossil of California.

California Law

The following information was excerpted from the California Government Code, Title 1, Division 2, Chapter 2.

CALIFORNIA GOVERNMENT CODE

TITLE 1. GENERAL

DIVISION 2. STATE SEAL, FLAG, AND EMBLEMS

CHAPTER 2. STATE FLAG AND EMBLEMS

SECTION 420-429.8

425.7. The saber-toothed cat (Smilodon californicus) is the official State Fossil.

Source: California State Legislature, California Law, , March 31, 2008.

Source: California State Legislature, March 31, 2008.

Source: California State Assembly: Office of the Chief Clerk, Archives, March 31, 2008.

Source: Statutes and Amendments to the Codes - 1973, Volume I, Chapter 792, Page 1409.

Source: California State Assembly and Senate: Final History -- 1973-74 Session, Volume II, A.B. No 940, Page 578.

Source: The Fresno Bee, Solon Seeks Law to Pick State Fossil, Tuesday, March 7, 1972,

Page A3.

Source: The Oakland Tribune, Bill to Make Tiger Official State Fossil, Friday, May 11, 1973, Page 77.

Source: Los Angels Times, California’s Pantheon: What Next?, June 11, 1975, Page A1.

Source: Stately Fossils: A Comprehensive Look at the State Fossils and Other Official Fossils,

by Stephen Brusatte, 234 pages, Fossil News (September 2002)

Source: State Names, Seals, Flags and Symbols: A Historical Guide Third Edition, Revised and Expanded by Benjamin F. Shearer and Barbara S. Shearer. Greenwood Press; 3 Sub edition (October 30, 2001).

Additional Information

Page Museum:

Web site of the Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits.

Ice Age Encounters:

The Saber-toothed cat comes to life.

What Is a Sabertooth?:

University of California at Berkeley Museum of Paleontology.

Saber-toothed Cat:

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

California State Fossil:

California Geological Survey - CGS Note 11-Saber Tooth Cat.

State Fossils:

Complete list of official state fossils from NETSTATE.

Stately Fossils: A Comprehensive Look at the State Fossils and Other Official Fossils,

by Stephen Brusatte, 234 pages, Fossil News (September 2002) The only book in print on the subject of state fossils, Stately Fossils offers an in-depth treatment of the natural and cultural history behind the official fossils of every state... and more! The book contains 80 photos and over 300 references to further information.

Prehistoric America: A Journey through the Ice Age and Beyond,

by Miles Barton, Ian Gray, Adam White, Nigel Bean, and Stephen Dunleavy. 192 pages, Yale University Press (February 8, 2003) When human beings first arrived in North America at the end of the last Ice Age, they encountered a teeming variety of animals, from ground sloths and mastodons to zebras and camels. This spectacularly illustrated book takes us on a captivating journey back to that time, showing us the entire continent and its incredible wildlife as it looked 13,000 years ago.

Ice Age Mammals of North America,

by Ian Lange, 226 pages, Mountain Press Publishing Company; 1st Edition (October 1, 2002) The time is the Pleistocene epoch, about 2 million to 10,000 years ago. Continent-size ice sheets cover 30 percent of the earth's landmass, and strange creatures rove the landscape. Ice Age Mammals of North America transports you to the world of saber-tooth cats, woolly mammoths, four-hundred-pound beavers, and twenty-foot-tall ground sloths.

National Geographic Prehistoric Mammals (National Geographic),

by Alan Turner, Reading level: Ages 9-12, 192 pages, National Geographic Children's Books (October 1, 2004) Budding paleontologists who take joy in tackling such scientific tongue twisters will glue themselves to the polysyllabic commentary accompanying this extensive gallery of extinct mammals. Working carefully from the latest fossil evidence, veteran science illustrator Anton has created finely detailed portraits of more than 100 vanished creatures, from early whales and tiny proto-shrews to Neanderthals.

The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives,

by Mauricio Anton and Alan Turner, 256 pages, Columbia University Press; New Ed edition (June 15, 2000) Paleontologist Turner and scientific illustrator Anton provide a unique and eye-catching account of living and extinct big cats. Following the introduction discussing their evolution, Turner offers detailed descriptions and differentiation of individual species. A close look at anatomy and its expression in the behavior of living big cats is used to make inferences about functions and behaviors in extinct species.

Dinosaurs and Other Mesozoic Reptiles of California,

by Richard P. Hilton, 356 pages, University of California Press; 1 edition (August 2003) California has produced a rich trove of Mesozoic fossils: dinosaurs, flying reptiles, and especially, since most of the state was submerged under water during the Mesozoic Era, marine reptiles. Hilton, a professor of geology at California's Sierra College, presents a comprehensive guide to these remains, and a history of those who discovered them, going back to the 1890s.

Fossil Treasures of the Anza-Borrego Desert,

by George T. Jefferson (Editor), Lowell Lindsay (Editor), 394 pages, Sunbelt Publications (January 2006) As the first comprehensive treatment of Anza-Borrego's fabulous fossil record, "Fossil Treasures" contains enough raw data and unsolved mysteries to keep scientists busy for the next 7 million years. (By then, of course, Anza-Borrego will have been transformed into an entirely new landscape.) In the meantime, it's the simple principle of juxtaposition - the mind-boggling contrast between the arid Anza-Borrego Desert of today and the lush landscape teeming with life that existed a few million years ago - that makes "Fossil Treasures" such a challenging and endlessly fascinating read.

|